Incomparable Impressionism Coming to MFAH

+8

+8 Incomparable Impressionism Coming to MFAH

Incomparable Impressionism Coming to MFAH

Traveling in Italy and missing Montmartre, Renoir said he’d choose the ugliest Parisian girl over the most beautiful Italian. His paintings however indicate otherwise. Lise, who modeled for over twenty of them, was stunning. Suzanne and Aline were no slouches either. It’s not certain which posed for “Dance at Bougival.” The painted figure resembles both Suzanne and Aline. Renoir may have combined the features of both women.

What is certain is that without entirely abandoning line and form, Pierre-Auguste Renoir used luminous color and skittery brushstrokes to render the nearly life-size dancing figures in the Impressionist style. Following a new sensibility, artists were experimenting with technique and subject matter. Thus, Renoir churned-out a color and light filled depiction of a gussied-up provincial couple shaking a leg with café patrons drinking in the background and matchsticks under foot. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston which owns “Dance at Bougival” weighed in on its steamy undercurrent. “The touch of their gloveless hands, their flushed cheeks and intimate proximity, suggest a sensuous subtext to this scene.”

Hot! It landed in Houston. On November 14, 2021, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston opens “Incomparable Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” an exhibition of 106 of the Boston museum’s most significant paintings and works on paper, through March 27, 2022. Ninety-one paintings and fifteen prints dating from 1830 to 1900 chart developments in French art, in which Barbizon, Impressionist and Post-impressionist artists made innovations in handling and radical subject matter to represent nature and contemporary urban life.

If as Professor Jack Flam told us, Paul Cézanne had an “aversion to” using nude models, Édouard Manet on the other hand plunged in. And knocked the traditional idea of a nude as a naked pagan goddess on its ear. Manet’s nude in “Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” called “vulgar” when exhibited, stares defiantly at the viewer. More provocative, the nude in “Olympia” glares comfortably reclined with her hand over her crotch. Today, these are priceless masterworks, too precious to travel, considered steppingstones to modern art. Victorine Meurent modeled for both. Manet painted Victorine eight times between 1862 and 1874. The exhibition features two paintings Manet made of Victorine. One is a straight-forward portrait in which Victorine wears the black neck ribbon worn by the nude in “Olympia.” In the other, Victorine is a street musician departing a café, carrying a

guitar, and eating cherries. Street musicians at sleazy cafés were unknown in academic art. Manet, not an Impressionist, reinforced for the Impressionists modern edgy subject matter.

Curators selected works to demonstrate influence, friendships, and collaborations. Eugéne Boudin’s fourteen marine paintings vividly exemplify these ties. Called an “immediate precursor of Impressionism,” Boudin parlayed penetrating observations of shorelines and harbors around La Havre into brilliantly executed portrayals of sunlight, atmosphere, waves, and boats, registering changes in hours and seasons. Not an Impressionist, Boudin was Monet’s teacher. He hammered Monet to closely observe nature

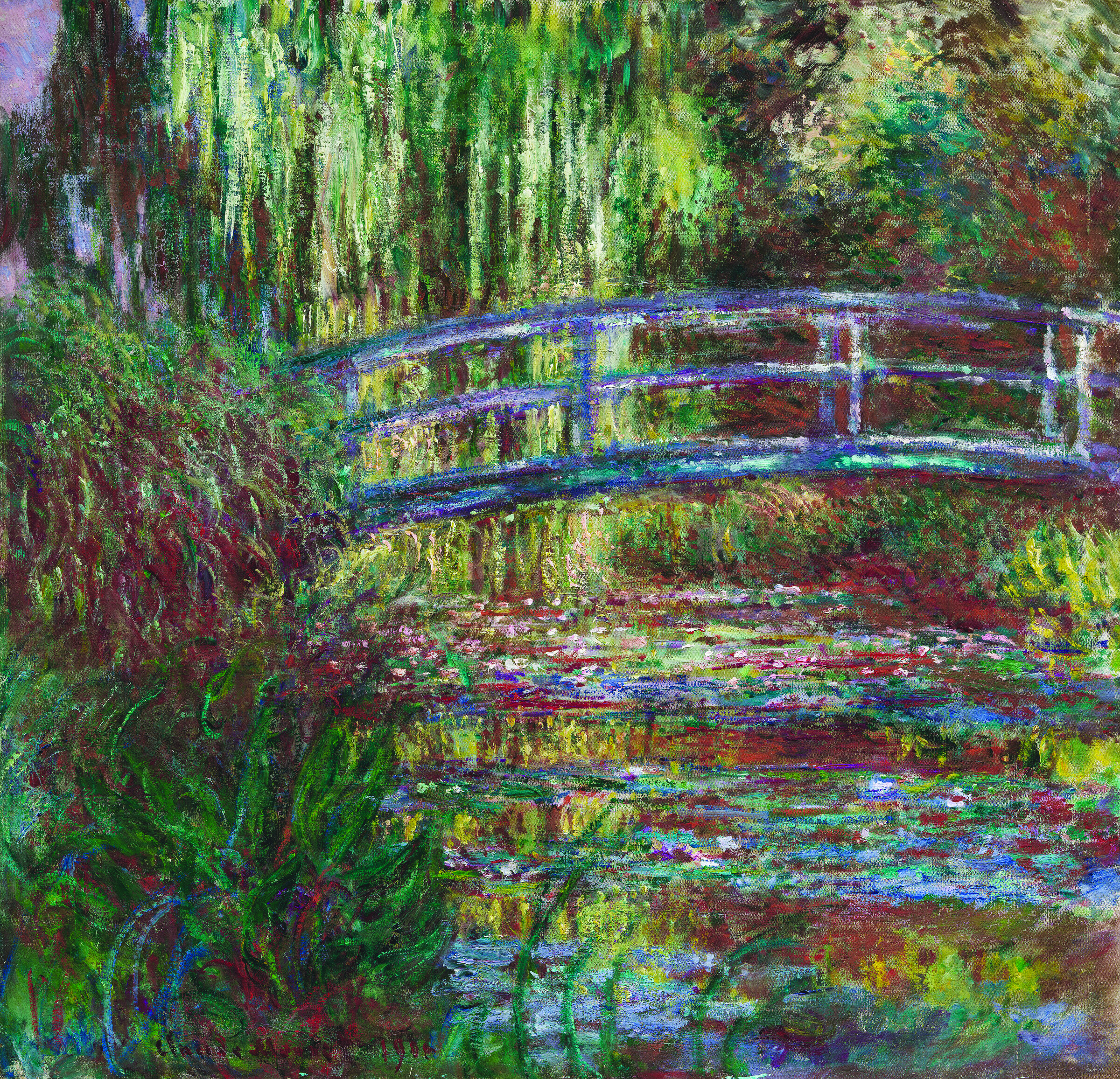

and see its beauty. At Boudin’s encouragement, Monet painted “directly on the spot.” Which led to experiments in capturing impressions of color and light, exemplified by the show’s Impressionist-style haystack. The haystack series typifies Monet’s distillation of mundane objects at different moments, to record momentary fleeting impressions. The

show includes a painting from Monet’s waterlilies series. Monet balked at leaving Giverny, nevertheless visited Venice to please his wife. He was determined not to work, yet the view of the Grand Canal and dome of Santa Maria della Salute from his hotel balcony was irresistible. The exhibit’s Venice canal scene shows loosely brushed light-splattered architecture and light-reflected ripely water.

Not an Impressionist, Henri Fantin-Latour made portraits of Impressionists. Fantin seems to have admired Manet, he copied “Olympia.” It is significant that Fantin introduced Impressionist Berthe Morisot to Manet, through whom she met Degas. Through Fantin, Morisot met Monet. The show’s four stiff-lifes by Fantin are not avant-garde subject matter, nevertheless his Chardin-inspired compositional arrangements feel timeless. Pulling from the observed natural world, he finagled a painterly approach with breathtakingly seductive color and texture. For Fantin, still-life was lucrative. Why change?

Gustave Courbet similarly raked in the bucks with floral still-lifes. He claimed to be “coining money out of flowers.” Not an Impressionist, Courbet’s unsentimental narratives of ragged peasants made him a guru of 19th century Realism. Courbet questioned Manet’s modeling of the nude in “Olympia.” He found the “Queen of Spades” too flat. But Courbet himself experimented with wide patches of paint. The show’s “Hollyhocks in a Copper Bowl,” has large flat passages, and areas of thick paint. The impasto’s abstract quality looks ahead to Modernism.

It was Cézanne who radically transformed the still-life genre. An original Impressionist who worked alongside Pissarro, in the end Cézanne abandoned Impressionism and conducted revolutionary experiments with still-life, landscape and human figures. The tilted tabletop in “Fruit and a Jug on a Table” lands us in new territory. Distorted forms, skewed perspective and unnatural color tones pave the way for newfangled developments like Cubist fracturing and planar variations, and Matisse’s expressive coloring. Cézanne ushers in modern art.

The show has eleven depictions of modern urban life by Impressionist Edgar Degas. I suggest you enjoy these, then grab the catalogue for the 2016 exhibition “Degas: A New Vision” by MFAH’s Gary Tinterow and Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre and of Musée d’Orsay. Its an exhaustive, exceedingly informative description of Degas’ art, which clarifies his interest in women in tubs, exhausted laundresses. or the exhibited horse races at Longchamps.

Alfred Sisley never deviated from the Impressionist style. The show features four paintings by Sisley. Sisley painted with Monet, Renoir, and Bazille in the Forest of Fontainebleau, near the village of Barbizon, guided by Barbizon landscapists. I once rode through the forest to see if those limestone boulders in their paintings were real. Bingo. Remnants from a geologic era when the forest was under water. If I could afford one of the paintings, it would be a landscape by Charles Daubigny. “Road Through the Forest” reveals Daubigny’s unmitigated proficiency at illustrating nature. Monet owned a Daubigny.

All iImages courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Picture Fund. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston / All Rights Reserved