“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

+6

+6 “Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

Niki de Saint Phalle, “Tir de Jasper Johns,” 1961. Plaster, wood, metal, concrete, newspaper, glass, and paint, 47 × 23 1/4 × 10 1/2 in. (119.4 × 59.1 × 26.7 cm). Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Donation 2005 from Pontus Hultén © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved. Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

Niki de Saint Phalle and Larry Rivers, “Portrait of Pregnant Clarice Rivers,” 1964–65. Collage, color pencils, pastel, graphite, and ink on paper, 61 13/16 × 44 1/16 in. (157 × 112 cm). Collection of Isabelle and David Lévy, Brussels. © Niki Charitable Art Foundation. All rights reserved. © Estate of Larry Rivers / VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

“Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” at the Menil Collection

The fact that men lorded-it over the art world in 1961 didn’t stop some women from scaling the walls. Even if patriarchal restriction of movement and expression made it a difficult thing to do. Birth control pills were only beginning to become widely available.

We got to meet Niki de Saint Phalle’s granddaughter Bloum Cardenas at the Menil Collection’s “media” preview of “Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s.” Bloum told us some interesting things about her famous grandmother. Saint Phalle, it seems, was puzzled that Picasso was rarely called Pablo, yet she was known as Niki.

Saint Phalle said she wanted the same freedom that men had. In 1961 she began attaching found objects and sacs of paint to her canvases and shooting them with a rifle. About her “shooting” paintings, the gurus at ARTnews noted, “The subversive overtones of the works – a woman utilizing a phallic object to destroy a canvas – were not lost on critics.” I think they’re saying Saint Phalle re-defined form by annihilating it. This was radical stuff in 1961.

“I was raped by my father when I was eleven.” Oh, the hypocrisy of insisting that women behave properly. Saint Phalle’s admission gave salivating theorists cause to approach her shooting art through the lens of severe trauma. However, the Menil Collection’s chief curator Michelle White believes that to be overly focused on biographical details brings a limited understanding of the artist’s work. There was a lot more going on than hysteria and cathartic release. Saint Phalle’s early 1960s “shooting” paintings signaled her participation in the newest developments in painting, sculpture, assemblage, performance, and conceptual art.

She “confronted” the art world it seems by dismantling the old farts’ traditional techniques and hierarchical notions. In the New York performance piece, The Construction of Boston, she shot a rifle at a metal and plaster Venus de Milo statue with paint inside, causing a classical art icon and a symbol of female perfection to bleed. I detect Monet’s beheading in Reims, a wall mounted rifle-shot depiction of a Gothic cathedral with plaster, found objects and vials of paint. Reims is grounded in seething objection to the Church’s control over lives, “another symbol of patriarchal power for the artist,” said curator White. When the de Menils purchased Reims in 1962, Saint Phalle expressed surprise that devout Catholics would want to own one of her cathedral pieces.

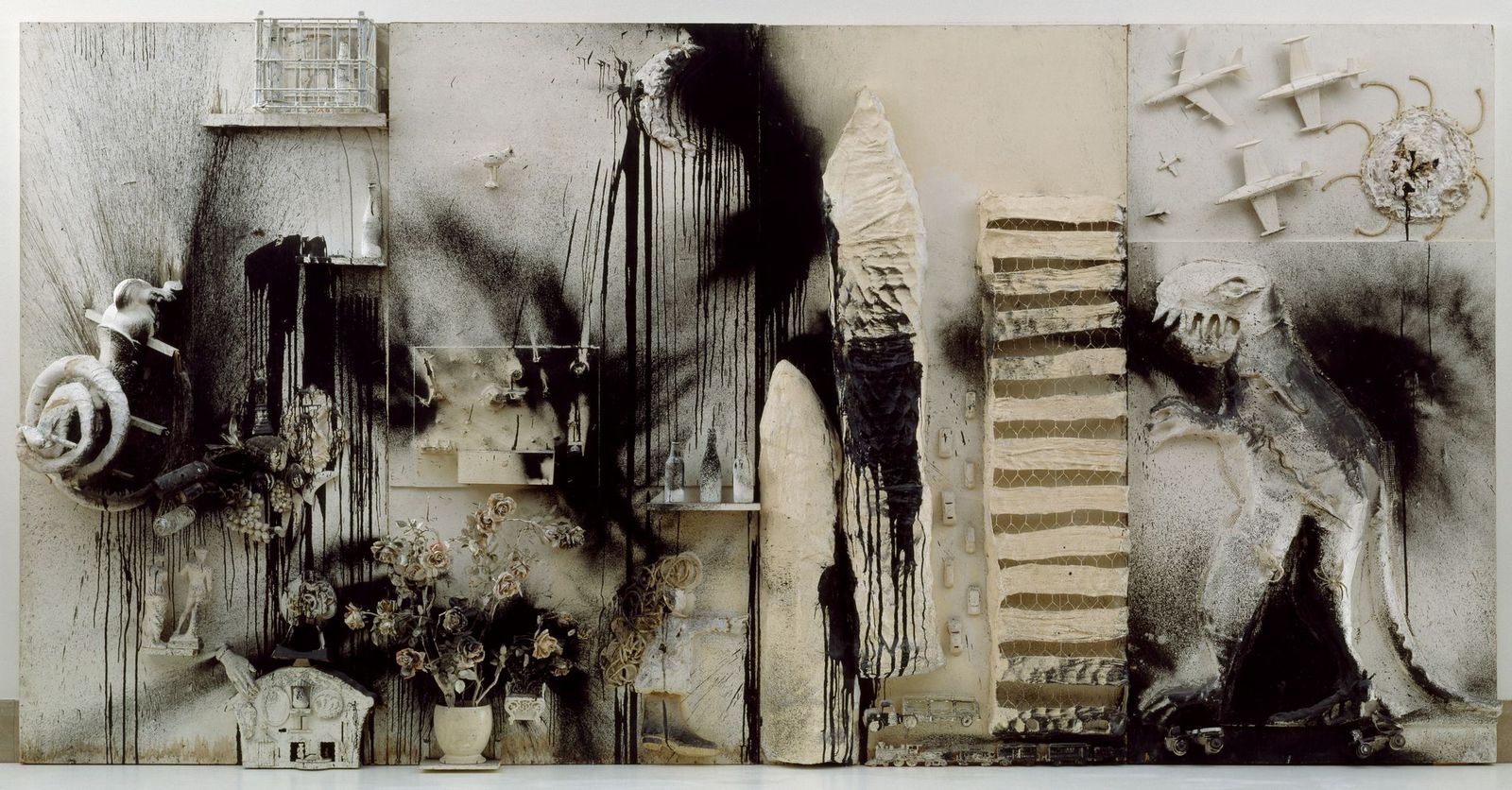

Just before their art world apotheosis, Saint Phalle’s friends Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg participated in her art. Johns was an integral part of Tir de Jasper Johns. The painting includes an image of his famed “target,” a can of paint brushes, and a light bulb. Johns shot the painting with a rifle, then signed it. Rauschenberg also did some shooting. The found objects Saint Phalle attached to her wall-mounted tableau places them in dialogue with Rauschenberg’s “combines.”

Several “destruction” paintings have renderings of prehistoric beasts in the process of poleaxing phallic-shaped American skyscrapers. Stacked associations include patriarchal authority, male violence and threat of nuclear weapons.

Artist Larry Rivers disclosed juicy stuff in his autobiography, his fondness for smack, for instance, and his bisexual hanky-panky. Rivers said he wanted his wife Clarice to get rid of the baby growing inside of her, however as Clarice’s belly “became distorted,” he got interested, and photographed her body in profile. From his photos, Rivers made a nearly life-size drawing of pregnant Clarice. Saint Phalle, who was Clarice’s friend and “close” to Rivers, collaboratively turned River’s graphite drawing into the colorful pastel and collage Portrait of Pregnant Clarice Rivers. “Clarice’s body appears as a fertile universe, teeming with flowers, butterflies, and decorative flourishes,” said the curatorial notes.

Portrait of Pregnant Clarice Rivers marks a stylistic turning point. With Clarice’s rotund body in mind, Saint Phalle discontinued the “shooting” and “destruction” theme and gradually shifted to three-dimensional representations of the female form. She called these sculptures “Nanas,” French slang for “girl,” but with edgy connotations. White, who worked for a decade to organize this show based on Saint Phalle’s most radical decade, believes the Nanas make a stronger statement than the destruction works. “A more powerful weapon to express what Niki felt was the female body.” In White’s estimation the sculptures are “more profoundly political.”

Initially, the sculptures were grotesque. The figure in a creepy wedding dress and veil, and the crucified figure wearing housewife curlers and hooker style garter belt question the “traditional and contradictory gender roles that she believed confined and endangered women.” Then their tone shifted to celebratory. With absurdly corpulent torsos and cartoony colors, the Nanas were posed to sit, dance and leap. All sizes, the most monumental Nana reclined with legs spread so viewers could enter its crotch. Papier-mâché and polyester-resin surfaces gave way to fiberglass and other industrial materials when the Nanas entered parks and outdoor public spaces. Puny heads on bulbous bodies gave them the quality of Paleolithic fertility goddesses. The figures oozed liberation and ferocity. Cumulatively, they form a bacchanal of empowered bitches.

Saint Phalle said the world belonged to men, and she intended to trespass into that world. I had to laugh when I read the Grand Palais’s statement at the time it showed her art. “Similar to Warhol, Saint Phalle was able to use the media to skillfully guide the reception of her work.” Looks like she figured out how to perch herself at the forefront of new art movements as well as how to straddle media hype and commercial strategy. I encourage you to read the essays in the exhibition catalogue, they are superb. “Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s” runs through Jan 23, 2022.