Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

+10

+10 Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure Opens at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Some will roll their eyes. It’s unsophisticated to carry on about such things. But to me, this insane part of the art world is exciting.

While MFAH’s Director Gary Tinterow was welcoming us to the preview of “Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure,” all I could think about was the February 2010 auction sale of Giacometti’s sculpture “Walking Man I” (1960) for a whopping $104.3 million. In 2010 “Walking Man I” broke the record for the world’s most expensive artwork sold at auction. Anyone witnessing that mouth-dropping sale at Sotheby’s in London, probably went straight to the bar. The auction house’s estimate was considerably lower than the sale price, and there was the added commotion of the purchaser bidding by phone, leaving everyone to speculate about which hedge fund dude or Russian oligarch or Middle Eastern collector had just snatched the sculpture. Turned out to be billionaire Lily Safra. Although, Giacometti didn’t hold the record for long. Three months later Picasso’s 1932 painting of a nude sold for $106.5 million. Soon after, it too got knocked out of the saddle by another record sale of an artwork at auction.

To create his sculpture “Walking Man I,” Giacometti cast several bronze versions. The Giacometti Foundation in Paris provided one of these for the museum’s show. It’s a stunning three-dimensional artwork. Consider this an opportunity.

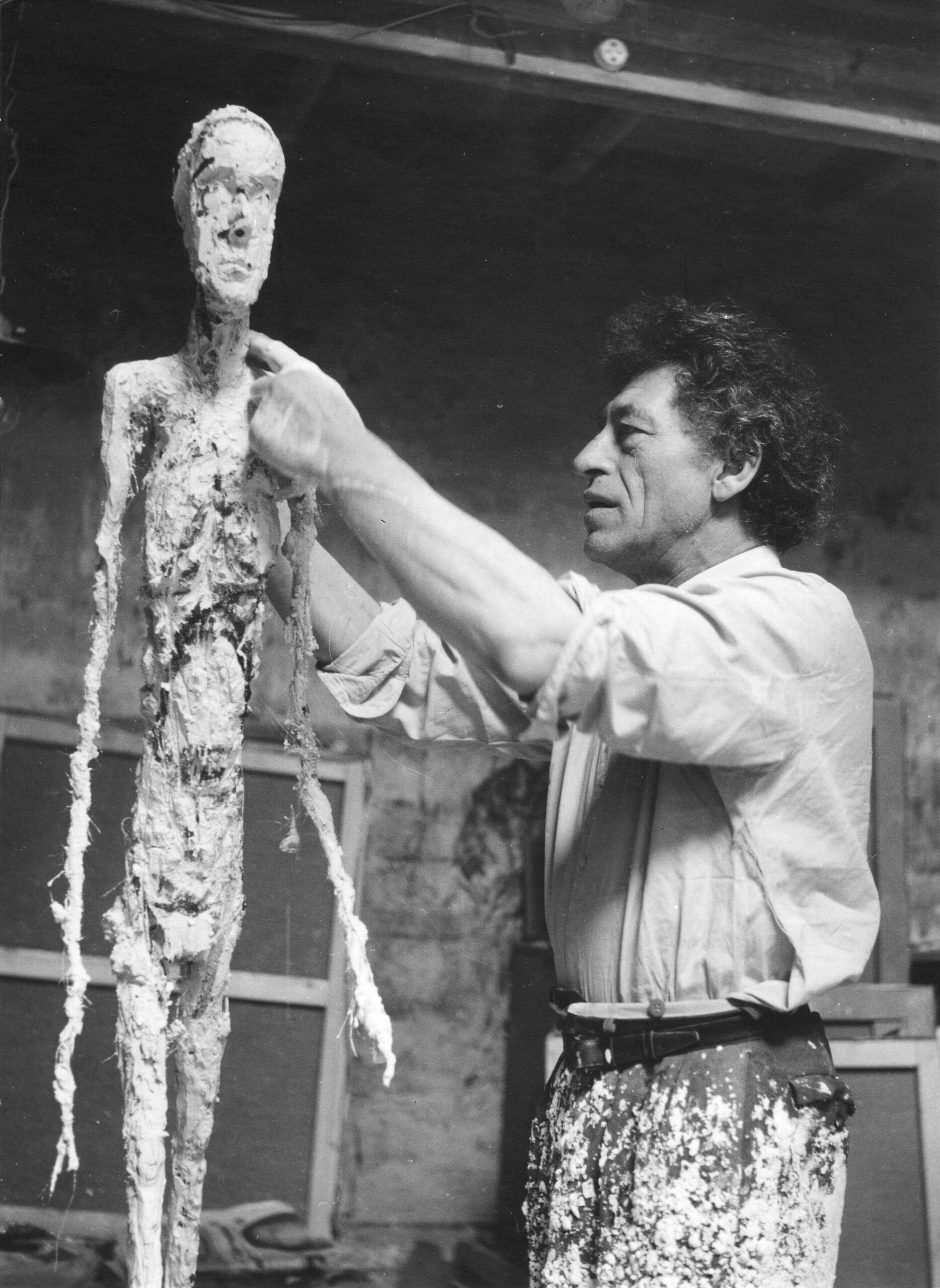

Do more than simply take in the fiercely original silhouettes of Giacometti’s attenuated figures walking through space. Check out their patina. The variety of textures and colors in the bronze surfaces will pull you in. Tinterow sighed when he spoke of Giacometti’s “remarkable sense of sculpture.”

Here’s what MFAH wants you to know:

“Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure” presents 60 masterpieces highlighting the artist’s major achievements of the postwar years (1945-66). Co-organized by the Fondation Giacometti in Paris and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the exhibition is co-curated by Ann Dumas, MFAH and Hugo Daniel, Fondation Giacometti and will be on view at the MFAH from November 13, 2022 through February 12, 2023.

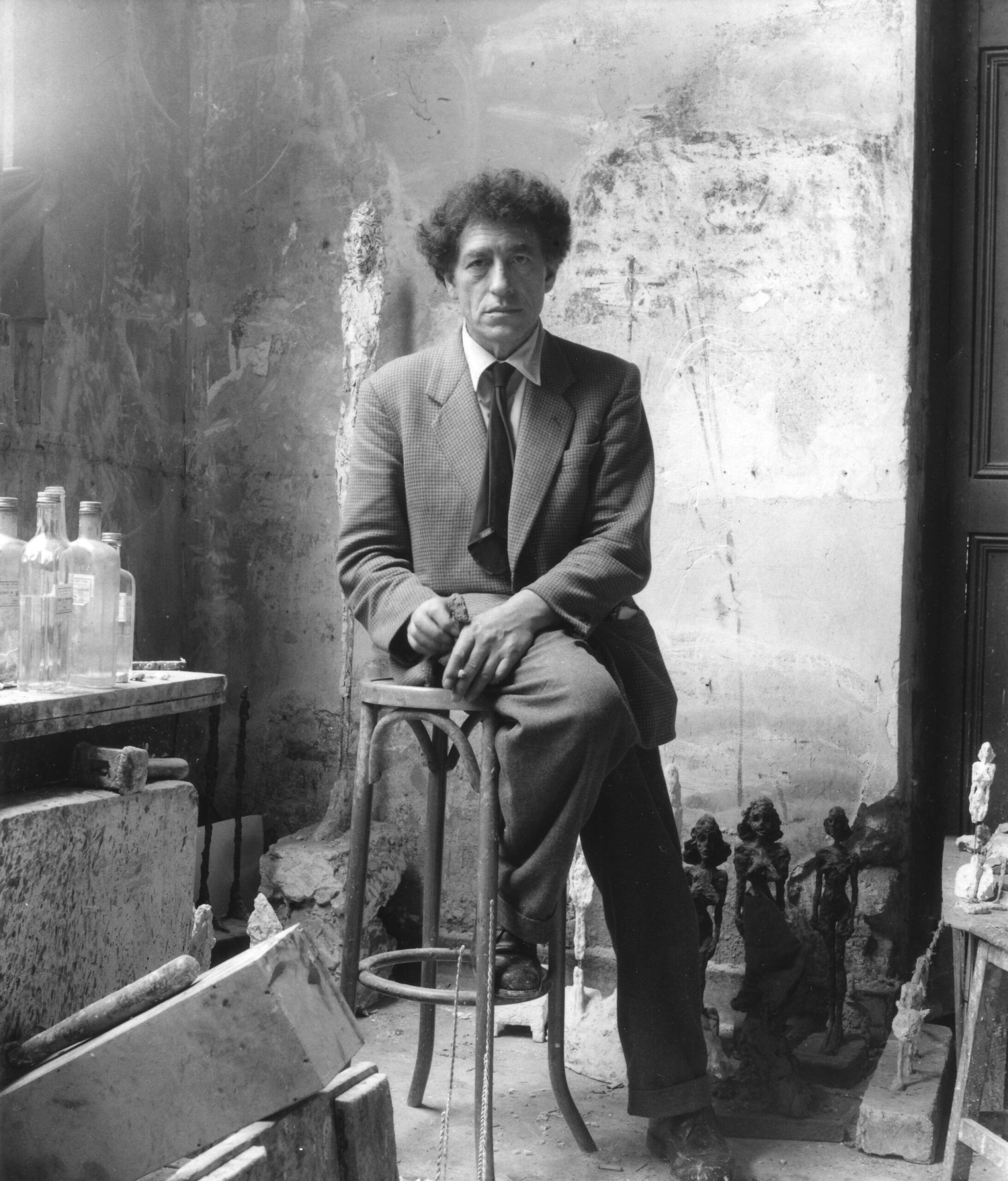

Widely acclaimed as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century, Giacometti (1901- 66) reasserted the validity of the figure and figural representation at a time when abstract art had become dominant in the international art world. His works became associated with existentialism; to many, Giacometti’s emaciated figures – evoking alienation, fear, insignificance and uncertainty – embody the psychological complexities of the Cold War era. Stripped to essentials, compressed and flattened, these fragile beings present themselves as expressions of a deep crisis facing art and humanity.

“Alberto Giacometti was a defining artist of modernism and of the 20th century,” said Gary Tinterow, Director and Margaret Alkek Williams Chair, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. “Toward the Ultimate Figure brilliantly explores Giacometti’s creative process to illuminate how he came to produce his iconic figures.”

Exhibition Overview

The exhibition is presented in 12 thematic sections that illuminate Giacometti’s focus on the human form and the development of his signature style.

Paris: Life in a Studio in Montparnasse

Born and educated in Switzerland, Giacometti moved to Paris in 1922, at 21, to study with sculptor Antoine Bourdelle at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Four years later, he began renting a studio measuring only 16 x 16 feet in a small house in the Montparnasse district of Paris. He maintained this legendary studio until his death in 1966 and produced the majority of his works there. After his death, the plaster walls he had filled with painted images were removed and preserved by his widow, Annette.

Obsessed with Heads

Like most artists of the period, Giacometti had been trained to draw and sculpt from live models. He became obsessed with rendering heads early in his career, but upon entering his Surrealist period in the late 1920s, he stopped working from models to instead invent images inspired by memories, dreams and hallucinations.

Into Thin Air

Giacometti was deeply concerned with the relationship between the figure and the surrounding space. He wanted his figures to appear as if viewed from a distance, stripped to essentials and devoid of any sense of narrative or anecdote. Giacometti advanced this concept in the late 1940s and 1950s by elongating his figures into filament-thin shapes that almost seem to disappear when viewed from certain angles.

On Solid Ground

Giacometti considered the base or platform an integral part of a sculpture. Determined to reinvent the most fundamental aspects of the medium, he explored ways of altering the size, scale and position of the base in relation to the figure. He also investigated methods of stacking several bases in ways that give even tiny figures a sense of solemnity and grandeur. Attaching his emaciated figures securely to a base or platform also introduced a contravening force to their progressive dematerialization.

Other Spaces: Landscapes

While known for his figural works, Giacometti also sketched and painted landscapes. During his later years, he merged the genres of landscape and figure representation. His sculptures “The Forest and The Glade” of 1950 contain multiple tall figures rising from a broad platform to suggest trees or wild plants growing in a meadow or clearing in the mountains. Faces and bodies in his figural sculptures also began to resemble boulders in a mountain landscape.

Creating a Myth: Giacometti Seen by Photographers

Giacometti’s reputation as a fiercely independent voice in the international art world was greatly enhanced by photographers who recorded and disseminated his image. Man Ray and Rogi André produced memorable portraits of Giacometti during the 1930s. Robert Doisneau, Gordon Parks and Arnold Newman photographed the artist with his sculptures in the studio in the 1940s and 1950s. Irving Penn and Richard Avedon produced portraits of Giacometti in the 1950s. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gisèle Freund and Yousuf Karsh contributed to Giacometti’s growing fame through their compelling images of the artist during the final decade of his life.

Alberto Giacometti: A Portrait in Film

In 1964 Swiss photographer Ernst Scheidegger began shooting a documentary film about Giacometti. Scheidegger completed a 25-minute version of the film in 1966 and released a 50- minute version in 1998. A frequent visitor to Giacometti’s Paris studio, Scheidegger produced a large corpus of photographs of the artist and his works. Selected excerpts from the 50-minute film are shown in this gallery.

Giacometti and the Literary Scene

Giacometti was intimately involved in the literary scene and wrote incessantly to express his experience of the world. He published texts in avant-garde journals and maintained close friendships with eminent writers, including André Breton, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Giacometti was also a prolific illustrator of poetry books. Several writers in his circle, including Jacques Dupin and Jean Genet, published essays and articles that contributed to the artist’s critical reception in the international art world.

The Human Condition

In the late 1940s, Giacometti’s art became associated with existentialism. Giacometti’s search for a universal art that would express the nature of the human condition emerges most clearly in his sculptures of emaciated figures trapped in a metal cage or walking in separate directions through empty city squares.

Models from the Inner Circle

Since Giacometti sought inspiration in the world around him, he needed models. But that was challenging, as he was extremely demanding, typically requiring the model to remain immobile in a closed position through multiple sittings that stretched over time. He frequently relied on close friends and relatives. Among his favorite models were his younger brother Diego and his wife, Annette.

Grappling with the Real

Giacometti’s struggle to resolve the tension between abstraction and naturalism is an ever-present feature of his paintings and sculptures. It appears in his portraits of the late 1940s and emerges in his sculptures of Eli Lotar, a photographer and friend, who posed for a series of half-length figures in the 1960s. Neither fully naturalistic nor abstract, his postwar portraits are infused with the same feelings of doubt and uncertainty as his standing and walking figures.

Standing Woman, Walking Man

Giacometti’s long search for the ultimate figure culminated in his large standing woman and walking man sculptures of the postwar period. He first began exploring these themes in a walking woman sculpture of 1932. He returned to the idea in the 1940s and created two distinct types: a standing woman and a walking man. By developing his figures in opposite directions, he accentuated the contrasting qualities of stillness and dynamism, timelessness and temporality. Subjected to a process of elongation, these thin, emaciated figures signaled a radical rejection of the weight and permanence of traditional marble sculpture.