Samuel Fosso’s “African Spirits” at the Menil Collection

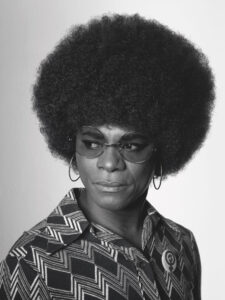

In 1970, the FBI issued a “wanted” poster for Angela Davis. It made a hefty impact, so much so that in some respects it overshadowed Davis’ 1972 acquittal for capital murder and kidnapping and distinguished career as a university professor, international human rights activist and writer. The myth of a menacing subversive lingered after exoneration. Intrigued, Nigerian-based artist Samuel Fosso borrowed details from Davis’ poster to stage his photographic self-portrait “Angela Davis.” He put on a mile-high afro wig, 70s-style gold loop earrings and a dress. Black liquid eyeliner is an astutely observed, penetrating detail by which Fosso, in a sense, embodied Davis. Such photographs are the reason Fosso is called “a man with a thousand faces” and regarded as one of Africa’s most important contemporary artists. “Angela Davis” is part of the series “African Spirits” (2008) at the Menil Collection through January 15, 2023.

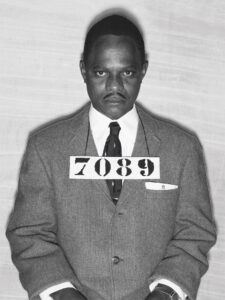

Conceptually, Fosso used his body and costumes to represent Africans and African Americans who rattled cages in the arenas of independence from colonial imperialists and civil rights, or used celebrity to sabotage an oppressive status quo. Wearing a gold medal for instance, he recreated the moment Tommie Smith raised a Black Power fist during the 1968 Olympic Games awards ceremony, radical stuff back then. The Olympics ousted Smith. To portray Patrice Lumumba, first post-independence prime minister of the Republic of the Congo, he wore a thin moustache and a white shirt similar to one Lumumba wore when arrested. Not long after he died by firing squad. The photos’ distinctive details, such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s Montgomery Alabama arrest mug shot, and Ethiopian Haile Selassie’s bald forehead and officious bearing, come from well-known, widely distributed photographs. A military coup whacked Selassie.

Here Fosso reflects on the idea of liberty as a moral imperative. Despite blow-back. And in some cases, even if by ruthless means. He said, “these figures were committed to the idea of freedom for black people in order to reclaim their culture and human dignity.” He “immortalized” them. He also dissects the power of iconic images and media manipulation. Celebrity as well. Also fashion and performance.

Here Fosso reflects on the idea of liberty as a moral imperative. Despite blow-back. And in some cases, even if by ruthless means. He said, “these figures were committed to the idea of freedom for black people in order to reclaim their culture and human dignity.” He “immortalized” them. He also dissects the power of iconic images and media manipulation. Celebrity as well. Also fashion and performance.

His grandmother was holding his hand. They were moving. There was shooting. She took a jacket off a dead man and “put it on me.” Fosso (b. 1962) told us this at the Menil. He was six years old when the Nigerian civil war began. He witnessed atrocities, burned villages. I wondered if wearing a dead man’s jacket opened him up to inhabiting another’s persona.

Hunger brought Fosso to Bangui in the Central African Republic. There in 1975 he opened a commercial photography studio. He was thirteen. When not shooting engagement portraits, he photographed himself. Self-portraits assured his family in Nigeria he was well. “I am growing.” Western magazines entering post-colonial Africa revealed the creative possibilities of props, makeup and lighting. One photo shows a muscular beefcake in a tight shirt, another a cocky shades-wearing celebrity. Fosso experimented like this from 1975 to 1978. Then began to work conceptually.

Things exploded in 1995. An exhibition in Mali won him an award. He won more awards. Offers to exhibit on other continents poured in. He had exhibitions, and entered prestigious collections in Africa, the Middle East, Europe and America, including London’s Portrait Gallery and Centre Pompidou. Tate Modern labeled his self-portraits “penetrative.” MOMA noted “intrinsic interest in studied self-presentation.” Germany’s Walther Collection hosted a full retrospective. Stockholm, Montreal, others. Fosso is in MFAH’s collection.

I’m watching Fosso smoke on the Menil’s sidewalk unaware that curator Paul R. Davis is introducing him, and thinking about some of his other series. “Memory of a Friend” (2000) for example in which he photographed himself naked and vulnerable to personally identify with his friend and neighbor who was murdered by armed militia during Bangui’s 1996-97 burning and looting. In “Emperor of Africa” (2013) he reenacted Mao Zedong. Like weirdo Andy, Fosso understood that the fat-face Chairman was a universally recognized iconic figure, and transformed himself into Mao with costumes and uncanny makeup. The series examines propaganda posters, as well as post-colonial economic realities. China is heavily invested in Africa. Imperialists continue to pilfer her natural resources. Africa’s “economic independence must follow political independence,” Fosso said reproachfully.

Fosso’s exhibition title is intriguing. Does he use the word “spirit” poetically? Some people are entuned to unseen reality. Their boundaries between the physical and spiritual realm are porous. The Igbo of Nigeria are like this. They’re not weirded-out by disembodied entities, and spirits of the ancestors. Fosso is Igbo.

It might be pertinent that in 2018 when grabbing an International Center for Photography award he said on video, “My body does nothing but transform a subject. A figure that I want to talk about. It has nothing to do with my body but maybe my spirit. My spirit, my spirit that follows the subject.”

Looking at the fourteen large-scale black and white photos put me in mind of something I read. Essayists detect a parallel between “African Spirits” and the Igbo ritual of costuming or “masquerading.” At its most trance-inducing, with drums and torchlight, the shamanistic practice manifests the spirit or ancestor invoked, for veneration, or more menacing purposes.

This association isn’t entirely convincing. Although I am convinced that the leopard skin and beads he wore to refashion himself as his grandfather, a village healer, for the 2003 series “My Grandfather’s Dream,” imparted a deep psychic connection to the man he embodied. “It’s a staging of the way of life I experienced as a child, a way of life that has since often haunted my dreams. Through my photography I interpreted what my grandfather wanted me to become: a healer and village leader. I did it to pay homage to my grandfather and to honour him.”

Fosso didn’t mention masquerading, but did tell us he was considered unattractive when very young because of leg paralysis. Self-portraiture convinced him he was attractive. He lives in Nigeria with his family and works in his Paris studio.