Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Presents Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith in January 2023

Two paintings depicting the Old Testament story of Judith slaying Holofernes—one by 17th-century Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi and the other by contemporary American artist Kehinde Wiley—will continue their national tour at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston from January 25 through April 16, 2023. Presenting Gentileschi’s Judith and Holofernes (c. 1612-17) from the collection of the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples and Wiley’s 2012 Judith and Holofernes from the North Carolina Museum of Art, Portrait of Courage: Gentileschi, Wiley, and the Story of Judith places the two paintings in dialogue with one another, revealing shared narratives and ideas across time and culture.

The subject of the two paintings, one that recurs throughout European art history, is taken from the Old Testament Book of Judith. The story features the heroic young widow who saves the besieged Jewish city of Betulia, which is under attack by the Assyrians. Judith determines to sacrifice herself in order to free the city. With her maidservant Abra, Judith sets out dressed in her finery to the camp of Assyrian general Holofernes, under the pretext that she is willing to betray the Israelites so that the Assyrians can defeat them. Enchanted by Judith’s beauty, Holofernes invites her to dinner in his tent, where she plies him with drink and he falls asleep. Judith severs his head with his own sword, she and Abra bring Holofernes’ head back to the city and the Assyrians flee.

The story of Judith and Holofernes—the vulnerable rising to slay a hostile invader, the oppressed overthrowing their oppressor—holds enduring appeal. Over the centuries Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome, 1593–Naples, ca. 1653), Judith and Holofernes, c. 1612–17, oil on canvas. 159 x 126 cm. Inv. Q 378. Napoli, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. Judith has been variously interpreted as a virtuous young woman, a seductive femme fatale and a brave heroine in depictions of this same scene by many artists, from Botticelli, Rembrandt and Caravaggio to Gustav Klimt. “I am thrilled to be able to share with our public Artemisia Gentileschi’s magnificent and compelling masterpiece, along with Kehinde Wiley’s brilliant reinterpretation of the legend of Judith and Holofernes,” commented Gary Tinterow, MFAH Director, the Margaret Alkek Williams Chair. “I look forward to seeing the reaction of our visitors to these two paintings treating the same subject, one by a woman, one by a man, separated by 400 years.”

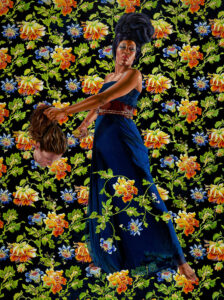

In depicting a woman in an act of courageous defiance, Gentileschi’s and Wiley’s paintings, though created 400 years apart, spur discussion around gender, race, violence, oppression and social power, allowing for reflection on contemporary issues through a historical lens. Gentileschi’s Judith and Holofernes is a powerful statement of her skill as an artist, which gained her much recognition in a male-dominated practice during her lifetime by patrons and commissions in Florence, Venice, Naples, Rome and England. But Gentileschi’s vision goes beyond the staging of a classical biblical story, through the unfolding of her own personal horror as a young woman. The daughter of a well-established artist, she was sexually assaulted by a family friend, and a very public court case followed, which caused Gentileschi to be perceived as a social pariah. Judith and Holofernes was painted the year of this trial, and can be understood as a statement of both autonomy and artistic integrity. Wiley is best known for his monumental portraits of young Black men and women placed in historical poses and settings appropriated from Old Master paintings. He consistently addresses issues of race within art history while also commenting on contemporary culture, gender, identity, power and inequality. Wiley’s Judith looks directly out at the viewer, holding Holofernes’ severed head. She wears a gown designed by Riccardo Tisci of Givenchy, who collaborated with Wiley on this first of the artist’s painting series, “An Economy of Grace” (2012), to feature female subjects.

Throughout his career, Wiley has consistently critiqued the racism of art history, while exploring contemporary street culture and identity. Reimagining classical portraiture while questioning who is represented in art history, Wiley states, “The whole conversation of my work has to do with Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977), Judith and Holofernes, 2012, oil on linen, North Carolina Museum of Art, purchased with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Hanes in honor of Dr. Emily Farnham, by exchange, and with funds from Peggy Guggenheim, by exchange, and from the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 2012. © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of Art and Sean Kelly, New York. power and who has it.” As in Wiley’s earlier work, the artist used “street casting” to find model Treisha Lowe, referencing for her stance another 17th-century Judith with the head of Holofernes, by Giovanni Baglione. Organization and Funding The exhibition is organized by the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the museum box.

Generous support is provided by: Bettie Cartwright Media Contact: Melanie Fahey, Senior Publicist, MFAH mfahey@mfah.org | 713.398.1136