Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Opens Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds

+1

+1 Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Opens Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Opens Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Opens Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Opens Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds

A fifteenth century Iranian blue and white dish with the image of a lion in Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds revealed itself incrementally. First I saw the animal’s rump, then noticed its implausibly angled facial features. It wasn’t until I spotted the sun disc symbol hovering above however that I understood its spiritual implications. The Koran emphasizes God’s meticulous ordering of the cosmos, with stars above and humans and animals below. It tells us animals like that lion know God created them. To call the lion dish’s blue coloring “vibrant” would be an understatement. Interestingly, the cobalt, lapis lazuli, and turquoise used in Persian ceramics were exported globally, some crossing trade routes into China.

I previewed MFAH’s new Hossein Afshar Galleries for Art of the Islamic Worlds. While showing us around, either Director Gary Tinterow or Curator Dr. Aimée Froom said the opening of the new galleries was “an extraordinary event in the history of our Museum.” If I can’t recall who, it’s because I was distracted by a late sixteenth century Iranian carpet, and in all honesty by the interesting people, which happens every time I attend one of those things. Regardless, there’s no denying the collaboration with Hossein Afshar is an extraordinary event in the history of the Museum. Think about it. A Kuwait-based bigwig with one of the most extensive collections of Persian art in private hands “endowed” six permanent galleries with nearly 6,000 square feet of space for art from historic Islamic lands, and forked over a thousand objects on long-term loan. Who wouldn’t call that extraordinary?

MFAH committed itself to displaying Islamic art years before opening the new galleries. In 2007, Tinterow’s predecessor Peter Marzio got the ball rolling when he realized the size and diversity of Houston’s Muslim community. Marzio roped in “Houston philanthropists with strong cultural-heritage links to historically Islamic lands.” Reading between the lines, this means high rollers with international connections and fundraising clout. It was Tinterow however who steered a “landmark” partnership with the renowned al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait. In 2012 Sheikha Hussa Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah and the late Sheikh Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah placed several hundred artworks from Islamic lands dating from the 8th to 18th centuries on extended loan into dedicated galleries. All the while, MFAH “strategically” added to the permanent collection. Now the new Hossein Afshar galleries nearly double space for Islamic art. Extraordinary indeed.

The Koran in my library has English translations alongside the Arabic verse. Arabic speakers would judge the translation pathetic. For them the English lacks the subtlety and lyricism that gives Koranic verse its extraordinary beauty. Moreover, a conspicuous publisher’s note warns that only by reading the Arabic will I get the full meaning of the revelations. Arabic. Yea, right.

Yet, when I read my Koran’s English “light” verse which begins, “Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth,” it doesn’t seem to suffer. This Sura poetically equates God with light, and stretches the association to lamps. Metaphorically and literally, light is a big deal in Islam, which explains the elaborate hanging lamps and standing candle holders typically seen in mosques and religious complexes. Hence, the beauty of the galleries’ sixteenth century Iranian brass torch stand (mash ‘al.) Safavid Empire (1501-1736) craftsmen engraved and inlaid such stands to hold candles in religious and courtly settings. Its inscription resonates with Sufi mystical expression. Sufis are Muslim mystics who seek oneness with God through disciplined practices such as asceticism and meditation. The inscription references a moth’s dying love for a candle, a metaphor for knowing God. A moth’s rush to death, in my interpretation, approximates ego annihilation consistent with the enlightened awareness some call God.

Muhammad was an illiterate caravan merchant who had a doozie of a mystical experience at forty years old in the year 620 AD. In a cave on Mount Hira, he perceived an otherworldly being ordering him to be God’s messenger. “Recite,” it commanded, which naturally freaked out Muhammad who hadn’t a clue what to recite. Things got spookier. On the horizon was a presence so overwhelming and terrifying, he crawled trembling to his wife Khadija and begged her to hide him. Ultimately, Muhammad submitted to God’s will and spent the next 23 years transmitting messages, often sweating and dropping his head between his knees. Devout Muslims believe he received divine revelations. Another possibility is he transcended the sensory self to a non-ordinary state of consciousness in which apparitions and clairvoyant downloads aren’t necessarily mysterious. Across the ages, all cultures have had similar experiences, usually interpreted in mythological or religious terms.

Regardless of if Muhammad channeled direct messages from an external deity, or drew awareness from a level of self akin to pure consciousness, his experience was so profoundly transformative it resulted in a mind-blowing piece of literature and a world religion. After the Prophet’s death in 632 his contemporaries recorded the revelations, presumably without the editing and redactions of other holy books. Notably the Koran includes God’s promise that the words the Prophet passed on to his followers are unaltered and free from falsehood and misinterpretation. It’s important to remember Qu’ran means “recitation.”

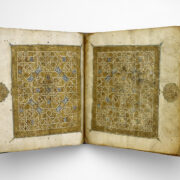

Accordingly, the Holy Book of Islam is prominently displayed in the galleries. See the fourteenth century Qur’an from Morocco. Its North African origin underlies the fact that Islam spread vast distances after becoming a religion. Written in Maghribi script on parchment, the illuminated manuscript has a colophon dating it 718 AH/1318 AD. “AH” means “after Hijra.” Hijra is the journey Muhammad and his followers made from Mecca to Medina in 622 with persecutors hot on their heels. One reason was the monotheism Muhammad preached threatened the economy tied to Mecca’s goddess cults. Historian Karen Armstrong wrote Muhammad’s enemies offered a reward of a hundred she-camels to anyone who brought him back dead or alive. Once in Medina, the Muslim community cohered. As a pivotal event in the spread of Islam, Hijra anchors the Islamic calendar. Thereafter, Muhammad’s political and military maneuvering helped spread the faith.

The Koran is the fundamental core of that faith. So it’s unsurprising Muslims venerate the calligraphic writing that transmits God’s messages. No wonder Islamic calligraphy is the most elevated form of Islamic art. Calligraphy means “beautiful writing.” Although even secular calligraphy has an aura of sacredness. It imparts blessings. Naturally, writing implements and accessories can be quite opulent. For instance the 16th century Iranian lacquer and gold pigmented Book Binding with depictions of figures seated and hunting on horseback in a garden reminiscent of a Koranic paradise.

Textiles are also a key component of the galleries. There is a stunning Shakhrisyabz Suzani (c.1800) from Uzbekistan. Traditionally made by female members of a bride’s family for her dowery, they essentially bring good fortune. This suzani’s silk thread embroidery renders floral and vine scroll motifs. Many include embroidered pomegranates to symbolize fertility. The day I visited, scarfs based on the Uzbek suzani were flying out the gift shop, which made me curious. Not sure how Museum agreements get hashed out, but will Hossein Afshar share profits from the merch?

Uzbek textiles are bewitching. I have a theory. Historians say that when Alexander the Great defeated the Sodgians in the Central Asian boonies (328 BC) and married their princess Roxane, she was the most beautiful woman the Macedonians saw while conquering the known world. Predictably after Alexander kicked the bucket, Roxane and her son Alexander got whacked to ensure the half-barbarian heir didn’t inherit the empire. Sodgia is part of modern Uzbekistan. I’m convinced Roxane’s colorful tunics and turbans dazzled Alexander. Researching Uzbek traditional costumes, I read the Sodgian regional style has embroidered motifs rooted in pre-Islamic Zoroastrianism.