Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

+6

+6 Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

Portals to the Divine: The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy Opens at the Menil Collection

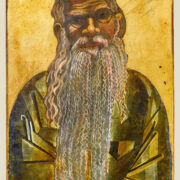

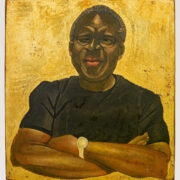

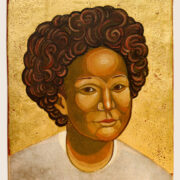

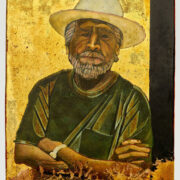

Imagine being a Christian icon painter in the early centuries of the Eastern Church. You’d probably be working in a monastery or church affiliated workshop, cranking out images of Christ, the Virgin or some important saints. Rather than handling these figures naturalistically, you’re guided by Eastern Orthodox stylistic conventions. Your figures for instance tend to be slender. Facial features are often distorted, with heavily creased eyes. Expressions are fiercely solemn. You employ weird perspective. Gold toned coloring saturates the panels.

There’s an underlying reason for not rendering naturalistically. Icons aren’t mere representations. They’re actual embodiments of divinity. Being covered with gold suggests a supernatural force, a notion firmly rooted in Byzantine Christianity’s deeper mystical strains. Things become precarious when icon worship is violently opposed. Approximately 200 years after Saint Augustine condemns it as demonic, Pope Gregory I (590 AD) grudgingly admits the images serve as teaching tools for illiterate Christians and for pagans. “What scripture is to the educated, images are to the ignorant.” A few centuries later however all of the iconoclastic flack dies down, and it’s OK to venerate sacred images. Needless to say, the icons perform miracles and cure diseases, and it is dumb to march into battle without the protection of these powerful panels.

A visionary Houston based artist makes contemporary portraits borrowing the stylistic framework of Eastern Orthodox icons. About fifteen years ago, Nestor Topchy (b. 1967) began an ongoing project of painting his friends. He uses the same techniques and materials by which the Ukrainian Eastern Orthodox Church to which he belonged has been churning out icons for the last 800 years. It’s quite remarkable. Topchy is not painting saints, he’s painting ordinary people. A few are known to be slightly strange, but let’s face it, they’re artists. In this, he intends deliberate mystification, regarding their images as conduits to other worldly realms. About representing his friends with sacred Byzantine icon language, Topchy said, “the portraits painted in the byzantine tradition create a portal through which the divine is reached. To paint a mortal in the sea of gold light, alone is to propose a saintliness that dwells within all people. To paint any man is to paint God’s face.”

It’s a big deal whenever the Menil Collection gives a one person show to a Houston artist. Trust me on this. On August 4, 2023, the Menil opens The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy. The show, Topchy’s first museum exhibition, will include over a hundred painted portraits. The Iconic Portrait Strand by Nestor Topchy runs through January 21, 2024.

Topchy said, “there is an inherent divinity in everyone.” My hunch is when Topchy throws out the word divine, he means consciousness beyond space and time that is the hidden, non ego-bound part of the self. The way I see it, Topchy is trying to remind us of the cosmic implications of being human.

Menil Senior Curator Michelle White elaborated on Topchy’s artistic process. After applying a base of red clay and powdered marble to cloth on a wood support, Topchy paints his portraits with pure pigments and egg yolk binder, then surrounds the figures with a layer of gold leaf. He also uses an assortment of organic materials like honey, beer, vodka, and cloves. He has said that his “process begins with the board. The wood is the tree of life, and the gesso is the bone, and the gold leaf is the spirit.” The final steps involve the application of ozhivki, meaning life-giving lines, that highlight or define the details of features, such as strands of hair or creases around the eyes. He then seals the work with oil.

Menil Senior Curator Michelle White elaborated on Topchy’s artistic process. After applying a base of red clay and powdered marble to cloth on a wood support, Topchy paints his portraits with pure pigments and egg yolk binder, then surrounds the figures with a layer of gold leaf. He also uses an assortment of organic materials like honey, beer, vodka, and cloves. He has said that his “process begins with the board. The wood is the tree of life, and the gesso is the bone, and the gold leaf is the spirit.” The final steps involve the application of ozhivki, meaning life-giving lines, that highlight or define the details of features, such as strands of hair or creases around the eyes. He then seals the work with oil.

Topchy begins by sketching each person. So interaction with the sitter is part of the process. It connects, he said, “the temporal, ephemeral moment with history and tradition, a gesture towards the immutable, the divine.”