Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

+3

+3 Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Fire and Sex: Living with the Gods at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

I’ve often suspected human beings are genetically programmed to seek the divine. In other words, it’s in our DNA to know the gods. Consider the fact that at this stage in our evolutionary development we cannot know reality. At the same time, dreams, intuition, precognition, out of body experiences and apparitions hint at wider reality. Could it be these deeper levels of consciousness account for our innately human yearning for the transcendent, and compel us to crank out objects that help us know god. Let’s face it, we’ve been building temples and making spiritual objects practically from the get-go. The earliest known temples were built at Göbekli Tepe 11,000 years ago. Archaeologists discovered an ivory statuette of a man with a lion’s head carved 40,000 years ago, which might be the oldest known man made object created solely for spiritual or ritualistic purposes.

Over the years I’ve seen unforgettable examples of man’s search for god. Machu Picchu’s Temple of the Sun for one. Equally memorable was the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, despite the god’s fundraising shenanigans, and even if the curvy road freaked me out. Pausanias warned the road to the sanctuary was “precipitous.” I once hot-footed it to Harran, south of Sanliurfa at Turkey’s Syrian border, where there between the Tigris and Euphrates in one of the oldest continuously inhabited places on the planet, had been an elaborate sanctuary to the Mesopotamian moon god. Also in Harran the Hebrew bible says, god commanded Abraham “arise and go,” which nudged the enterprise toward settlement in Canaan. If Abraham’s historical veracity is murky that’s irrelevant, what’s important is the patriarch’s followers’ belief in the literary narrative catapulted a world religion. Three actually. The other “Abrahamic” religions have ties to Harran, archaeologists recently excavated a fifth century Christian basilica, and there are archaeological ruins of the Great Mosque, constructed less than 150 years after Mohammad died.

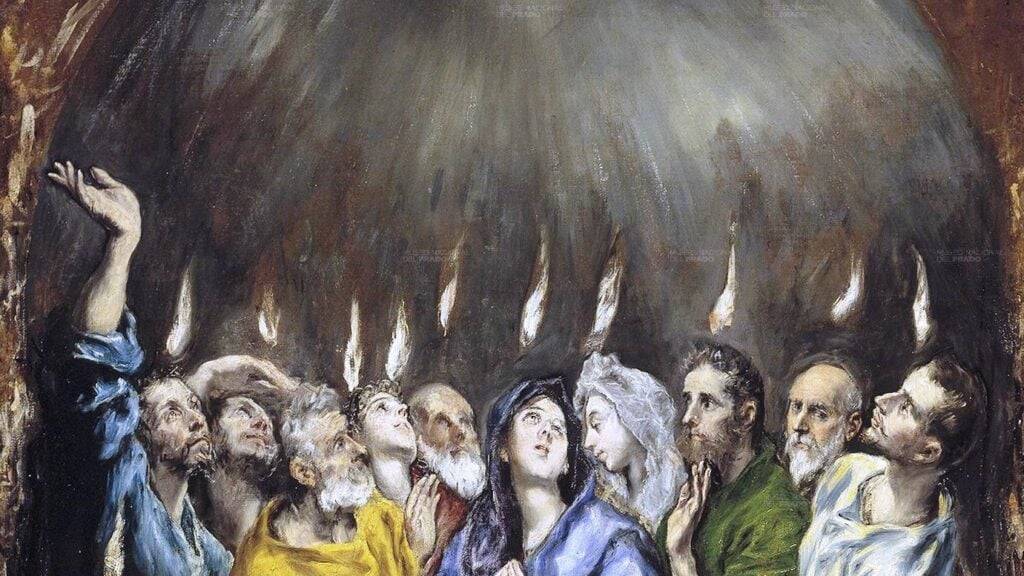

At MFAH, you can see a startling example of man’s yearning to penetrate the divine. El Greco’s painting “Holy Fire: Pentecost” (c.1600) depicts Jesus’s apostles gathered in Jerusalem after the crucifixion. They’re portrayed in ecstasy and trance brought on by an other worldly vision, weirdly described in “Acts” as spirit descending on them like “tongues of fire.” Several figures appear so unhinged they nearly topple over, which aligns with the fact that it would take a mind shattering apparition to convince the apostolic gang that some aspect of Jesus had indeed managed to return.

Why did our Museum navigate arduous insurance requirements to slam dunk a masterpiece that rarely leaves the Prado? Because British art historian Neil MacGregor created a 2017 BBC radio series and published the book “Living with the Gods” about objects and artworks utilized in mankind’s spiritual search. MFAH invited MacGregor to organize an exhibition based on the “gods” theme using objects from the Museum’s permanent collection and borrowed from other collections, to coincide with the Museum’s 100th anniversary. “Living with the Gods: Art, Beliefs and Peoples” on view through January 20, 2025 includes 200 objects made over 4,000 years that help humans connect with the divine, which is essentially connecting with ourselves.

Years of watching from a distance convinced me museum director Gary Tinterow had the clout to phone the Queen of England or the Pope and finagle an art loan. “Sure Gary, no problem,” they’d say. MacGregor reinforced my observation at the preview. He applauded Tinterow for lassoing the El Greco, as well as a rare icon owned by Saint Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sanai, and an absurdly large silver vessel that held sacred water from the Ganges in the collection of the Maharaja of Jaipur. “Nobody says no to Tinterow,” MacGregor said with satisfaction. Prior to this, Tinterow had introduced MacGregor as one of the world’s great minds.

One of the world’s great minds guided us through the galleries and pointed out the spiritual significance of each artifact. He showed us for instance a large silver “Afarganyu” (1917) which is a vessel for holding fire. In Zoroastrian tradition, fire represents god. Associated with purity and divine light, fire is so sacred practitioners worship it by maintaining a perpetually burning flame. This vessel, which originated in an Agiary or fire temple located on the Indus River in Sukkur Pakistan is displayed in the exhibition’s “Fire” gallery. Near it, are leaves MacGregor claimed came from the burning bush, an ancient bramble bush on Mount Sinai that tourists believe is THE burning bush. As I tried to visualize a burning bush that doesn’t burn up telling Moses to deliver his people from Egypt, I thought to myself how refreshing to attend a preview and not have to hear the typical chatter about art techniques and styles and categories. Instead we heard about the object’s purpose, a purpose integral to our search for ultimate reality.

There’s a real hodge podge of objects. An Islamic mosque lamp, 4000 year old Cycladic fertility figurines, bronze crucifix by Bernini, 3500 year old statue of a Phoenician storm god, statuette of Isis nursing Horus, west African Bedu Mask associated with the moon and dead ancestors, carved marble Venus, Hanukkah lamp and a Peruvian beer drinking cup shaped in a god’s head, only scratch the surface. Collectively, these artifacts strongly reinforce the fact that humans cannot live without their deities. Case in point, how quickly the cult of the Virgin Mary replaced the cult of the virgin goddess Artemis after Artemis’ Ephesian temple was demolished.

Spend time with the Hindu god Shiva. Shiva is the reality behind existence, an unknowable immensity, the absolute source of all things. This divinity represents the energies of the cosmos. Manifesting as Nataraja, surrounded by fire, Shiva dances in a perpetual cycle of creation and destruction, with one foot on the fat guy ignorance, and the other raised in bliss, while the Ganges pours from Shiva’s hair. In other incarnations, Shiva articulates as both male and female. Although having sex with Shakti brings the cosmos into being. With proper devotion at Banaras, the god can help you escape rebirth. Shiva is way old. Archaeologists discovered a seal with Shiva’s image that locates the deity in the Indus Valley before Aryan beliefs and practices entered northern India, suggesting the god predates the written Vedas.

www.mfah.org