Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

+6

+6 Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

Big Bang: Penny Cerling’s Intricate Drawings – Interview

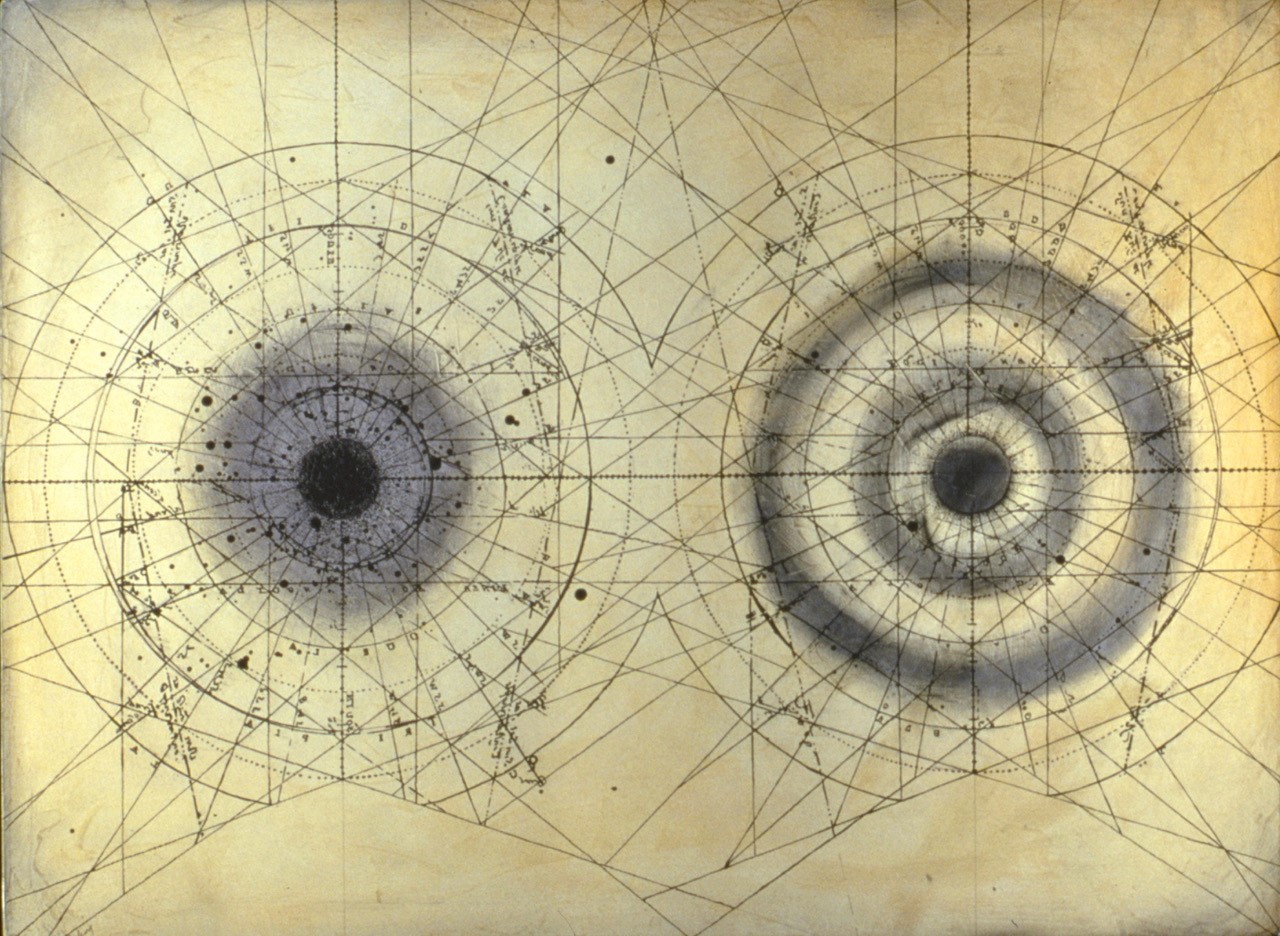

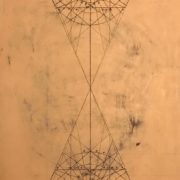

When it comes to the big bang, I feel excited and weirded out in equal measure. The minute I saw reference to it in Penny Cerling’s art, I poured a glass of bourbon and pondered the philosophical implications. Years ago, my egghead friend Fernando Casas who is a professor of philosophy, explained to me that philosophy is an attempt to know who we are, where we are, and why we are. Philosophy and art, Fernando said, “are interwoven,” because art is a philosophical endeavor. (Ditto science.) Framed against Fernando’s assertion, Cerling’s pen and ink drawing “Black Hole and Big Bang” endeavors, through poetic expression, to know who we are, both cosmologically and molecularly.

Accordingly, she deciphers the ungraspable event that began the universe, as well as time and space. Simply put, during a period of cosmic inflation about 13.8 billion years ago, all matter was concentrated in a single point of infinite density. Something cataclysmic made it begin to cool and expand. Immediately, particles formed, which led ultimately to stars, galaxies, the cosmos, as well as miserable little us, by way of crawling out of primordial pond scum. Included in this big bang narrative is the formation of the first atom, the link to us.

Insofar as one circular form references big bang, you can bet your beer money the other alludes to another singularity, black hole, also a point of infinite density where space and time do not exist, usually caused by a dying star’s gravitational collapse. Turn you eye to the linear and graphic compositional elements that surround the circular forms, it’s tempting to associate them with subatomic particles like quarks and neutrinos which existed at the beginning of the universe, and which like black holes, defy the laws of time and space. Subatomic particles turned general relativity on its ear and spooked Einstein, however they make up our universe, and are in us.

If you ever find yourself milling around Topkapi Palace, be sure to check out the Third Court. This section of the palace is arguably one of the most interesting, one reason is it contains the Prophet’s sacred relics, a tooth, some beard hair, his sword, and his mantle or cloak. Another is, it has sundials, such as the elaborate contraption that dates to the 1480s. Cerling’s encounter with a Topkapi sundial plunged her headlong into research. With time, she widened her investigation to the construction of sundials, to time pieces from antiquity, which led to Einstein, which predictably led to black holes where time doesn’t exist. She scrutinized multiple historical illustrations and models of sundials. “One sundial pattern captured my imagination and I’ve used it repeatedly, cutting, splicing, adding, subtracting.”

When I heard Redbud Gallery in Houston was exhibiting over twenty of Cerling’s intricate pen and ink drawings in “Penny Cerling: Cycles” through January 5, 2021, I contacted her to ask a few questions.

Virginia Billeaud Anderson: After sorting out big bang and sundials, you hunkered down to study plants, saying that ever since nursing school you wanted to understand more about the evolution of plants. Your research led to a four part series that pictorially imagines the role of lignin, a substance in plant cells, in the evolution of plants.

Penny Cerling: I was thinking about the evolution of plants and animals: how could either leave water? Everything started in water. It is thought that red algae is the place where “plants” developed the mechanics (lignin) to leave water and move to land. They developed early rooting systems to obtain fluid and nutrients (transportation), and eventually produce seeds which need lignin (for protection of genetic information). Lignin is hard to break down, yet the termite has chemistry in its gut to destroy it (destruction.) I like that this four part series explores the role of lignin in plant evolution from beginning to destruction. My work is frequently about cycles.

VBA: I recognized sundial patterns in one of the lignin plant images.

PC: After all, the sun, like water, plays a big role in evolution. I also incorporated mechanical engineering drawings in the image “Structure Lignin Transportation” to convey power and motion.

VBA: It’s fun to imagine you gawking at plant cells under a microscope.

PC: I didn’t examine the plant cells, or algae for that matter, under a microscope, I don’t have a good one. I’m a docent at Houston Museum of Natural Science and spend a lot of time giving tours in Paleo. The museum has laid out the Paleo department beautifully, starting with the earliest evidence of life (bacteria) and continuing to human evolution. I found that evolutionary space between trilobites and plants very interesting and was curious about the very early gorgeous plant fossils with no bite marks, so I started looking up plant evolution on the internet. Still not sure about the bite marks – but other critters had to evolve to eat the new stuff anyway and aren’t termites horrifyingly amazing?

VBA: I remember the recent Bur Clover series, exhibited at Houston Baptist University in 2018. Sexy spiral designs appeared in some of the bur clover drawings. By the way, your skillful handling of line has been compared to Leonardo.

PC: That show was about the bur clover which is a pesky little weed which a friend insisted wasn’t a weed, so I pulled it up on a damp spring day and found the nasty bur, appearing to be intact, between the leaves & roots. Intrigued, I brought it into the studio and found it to be a beautiful spiral – the further I explored the more I found and eventually discovered that it is a legume, attracting a bacteria to fix nitrogen in the soil. Basically, I found myself going from a pest to the essence of life – a surprise and a rich source to mine. From pest to necessity!

VBA: Not surprising to learn there are scholars in your family, a fact which informs your work. Your ex-husband worked on the Early Man Project in Kenya with Richard Leakey, which provided you with the opportunity to interact with scientists in the field. You have regular discussions with your son Lewis Bowen, professor of Mathematics at the University of Texas, who works with entropy theory, ungraspably complex. As well, frequent exchanges with your brainy brother Thure Cerling, a professor of geology, geophysics and biology at the University of Utah. Thure’s examination of carbon isotopes in fossilized tooth enamel revealed early humans (hominine) and their ancestors shifted from an ape-like diet to a grass-based diet about 3.5 million years ago, which accelerated human evolution. Reading about your brother’s research made me wonder if the famous hominine Lucy, whose 3-foot high skeleton suggested bipedalism preceded human brain growth, fancied the new grass diet.

PC: I’m still wrestling with my son Lewis’ ground breaking ideas on entropy, I try to understand, he can no longer explain to me, my mind boggles. Thure is a pioneer in isotope technology. From his work on C3/C4 grass evolution came my series on grasses, from Lewis’s work on entropy, my series on knots.

VBA: You, yourself taught at a university.

PC: Graphics. At the University of St. Thomas, I worked with Earl Staley, David Gray and others who would be lifelong friends and colleagues. I stayed on part time for maybe three years.

VBA: I’m having a memory of when I worked at the Printing Museum and witnessed the people in the etching and lithography studios get excited when you visited. You were the big cheese, Penny. So was Suzanne Manns, who by the way, taught you etching at Glassell. Speaking of which, what better indoctrination for your gig at Little Egypt Enterprises print shop, where for a decade you worked as an etching printer alongside Tamerind-trained fine art printmaker Dave Folkman. The work involved collaboratively printing with Texas artists, many of whom were hot shots. Today much of that print art resides in museums and important private and corporate collections. In his 2019 exhibition of Little Egypt’s output at Glassell, art historian Pete Gershon labeled the print studio “one of the city’s most significant, imaginative and longstanding collaborative art projects.” Pete’s exhibition gave viewers the opportunity to see prints you made with Bob Camblin, Lucas Johnson, Charles Schorre, Derek Boshier, numerous others. That must have been satisfying.

PC: I worked with so many artists.

VBA: Gershon’s interview solicited from you the informative comment that your work involves mostly thinking about things. You told him the work represents musings about the things we can’t see but are happening around us and make the world go around. Anything you want to add?

PC: My work is about my awe and curiosity and attempts to understand rather than correct scientific anything. I think and draw, it’s more dream than real, perhaps.