Rick Lowe Moves the Needle on Community Support and Art

Any way you look at it, the MacArthur “genius” grant is an eye-popping award. With no strings attached. MacArthur Foundation gives $625,000 to an artist or writer or scientist so he will keep doing what he does. Houston artist Rick Lowe (b. 1961) said he was “completely floored” when he received it in 2014. One year before, President Obama appointed Lowe to the National Arts Council which advises the National Endowment for the Arts. These and a myriad of other honors befell Lowe for transforming 22 abandoned row houses in Houston’s Third Ward into the nonprofit Project Row Houses (PRH.) The organization hosts art exhibitions and residencies, education, a young mothers’ residential program, and a business incubation program. As gentrification pushes out low income residents, PRH punches back by purchasing, renovating, and leasing out at affordable prices. It partners with owners to preserve historical properties.

Shyriaka Morris’ participation in PRH’s mothers’ program helped her earn a doctorate. Others landed law degrees. Last month, when the Ford Foundation forked over $3.5 million, it called PRH “a cultural treasure.” The New York Times just ranked it 14 on its list of the 25 most influential works of “protest art” made in America since World War II.

“If you think about it, Rick sacrificed his career during that time.” Artists Floyd Newsum and Bert Samples are discussing the cradle days of PRH in an interview with Maria Gaztambide. In 1993, Rick Lowe, James Bettison, Bert Long, Jr., Jesse Lott, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples and George Smith tossed around ideas about an exhibition venue that would positively impact Houston’s African American communities. Lowe believed the row houses served their purpose. Samples recalled arguments. “Rick was the catalyst, had swell ideas, and Jesse was what I would call on the basketball court, the enforcer, holding Rick accountable for what he’s gonna accomplish, and he wasn’t just challenging Rick, he was challenging all of us. That was where I think we first saw ourselves as a group, not knowing what we were gonna do,” yet committed.

Newsum recalled nasty dirty work. While removing debris under a row house, his clothes got covered with black specs, “they were fleas,” but he figured fleas were better than discarded drug needles. “This institution brought the whole community, the city, from River Oaks, to Memorial, wherever, every race, class came together to help us, to unify, to transform this area. It was Rick who really was the force, if it had not been for Rick, PRH would not be what it is.”

One imagines their discussions helped Lowe communicate his vision. And primed him to collaborate with volunteers, donors, grant writers, foundations, ultimately a professional staff. Factor in innate talent for chatting up others. The middle child in a large family learns to maneuver.

Throughout, he considered PRH part of his artistic practice. This fits comfortably within the post-modern era’s broader definitions of art (which idiotically included body functions.) Lowe’s expanded definition rests on community engagement and revitalization. He extrapolated from German artist Joseph Beuys’ idea of art as participatory activities that shaped the world around us, which Beuys labeled “social sculpture.” Lowe applied social sculpture to community. He said artists like him who enhance communities are pioneers, for expanding notions what art can be. The New York Times labeled PRH the most original and ambitious work of art of the past century.

An additional factor set Lowe on his path. Disillusioned with the politically loud figurative art he was making, in 1992 he closed his studio and searched for authentic expression. It resonated that row houses, an architectural form rooted in Africa, held iconographic weight in his teacher Texas Southern University Dr. John Biggers’s paintings. Doc Biggers imbued row houses with “beauty, poetry, inspiration.” Third Ward row houses, he figured, offered a chance to merge activism and art.

Is his rural Alabama family proud of his accomplishments? “Art stuff” doesn’t interest them, they’d be more impressed if he was helping to pick peas and okra.

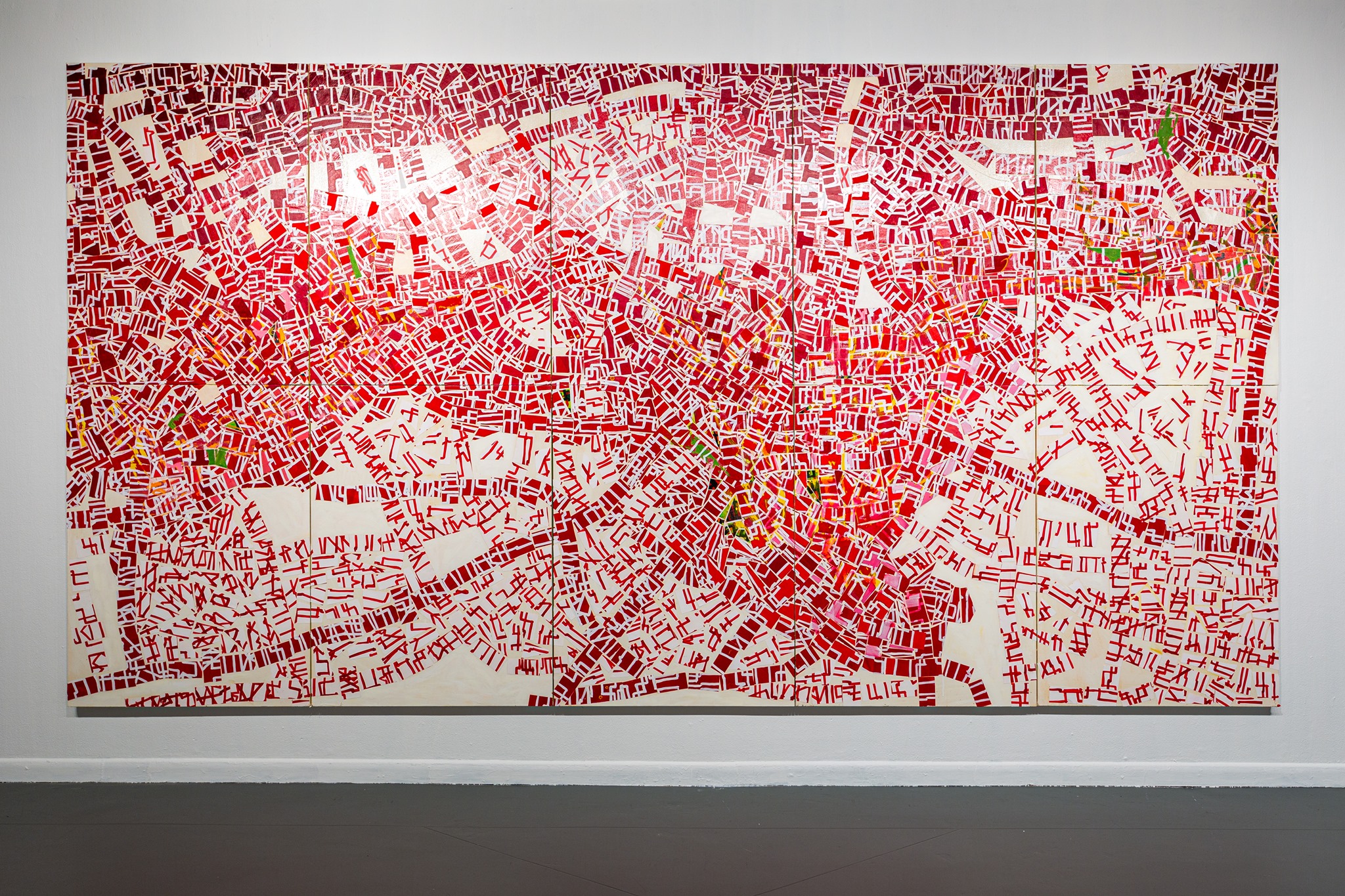

In 2018 Lowe handed over the castle’s keys to PRH staff. And moved on to other community improvement projects, including Los Angeles, New Orleans, Dallas and Athens Greece. He received prestigious fellowships, such as Harvard and MIT, and is currently a Professor of Interdisciplinary Practice at the University of Houston. Back in the studio, he cranks out aesthetically elevated paintings and drawings concerned with formal properties of color and form. In September, Art League Houston named Lowe its 2020 “Artist of the Year.” Don’t plop yourself at Art League’s door like I did, it’s locked for virus, but the on-line appointment process is totally painless. Soon I was gawking at an orgy of color in the exhibition “Rick Lowe: New Paintings & Drawings” through April 24, 2021.

It’s takes guts to use pink. Lowe rendered it seductive by offsetting cooler tones. Collage texture is wicked, his painting surfaces have smoothness and tactility in equal measure. Most interesting, his art is inspired by the domino games he plays with Jesse Lott at PRH, battles Lowe described as ratcheted up with noisy bluffing and table clattering, and which have “physicality.” Sketched domino patterns are starting points for new artworks.

My instinct tells me the domino shapes in the supposedly non-referential abstractions are a soft-core reference to community. Lowe likened the patterns to neighborhood maps. It’s not farfetched to associate them with the urban planning concept of “red lining” in which mortgage companies penalize low income neighborhoods. Nor, with the old men who play dominoes under trees, know everybody’s business, and offer valuable insight into neighborhood goings-on. Forget nit-picky distinctions between pleasure driven art and social content art. The entire shebang has spiritual gravity.

In 2009, Lowe overlapped community engagement with photography. I was taken with the photo “Brother in Law” of a spiffed-up dude holding a plate of grilled chicken, and mentioned it in a newspaper article. I assumed at the time his subject was a popular restauranteur, but learned later he had returned to Third Ward after serving over twenty years in prison. His pre-prison dream was to own a restaurant, so Lowe staged him like he lived his dream. Mirroring the row houses’ shift from connotations of blight to positive symbols, he said he re-branded the guy into a positive symbol.

VIRGINIA BILLEAUD ANDERSON